Feline Coronavirus (FCoV) and Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP): Towards a reliable diagnosis

Posted On: 02/03/2025

About PIF

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is an RNA virus widely present in many cat populations worldwide. Primarily a virus affecting the digestive system, it generally causes no clinical symptoms or manifests itself only as mild enteritis, or even delayed weight gain. However, a small proportion of infected cats develop a serious disease, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). FCoV genomes like all coronaviruses, exhibit high genetic variation due to the high rate of RNA polymerase errors, resulting in different types of mutations, such as point mutations, deletions, introduction of termination codons, and recombinations. Although FCoV can spread systemically in the monocytes of healthy cats, it is hypothesized that specific mutations, occurring in a given cat, allow the virus to switch its cellular target from enterocytes to monocytes, facilitating the emergence of a highly pathogenic form of the virus responsible for FIP. However, no specific mutation has yet been identified, and it is unlikely that such a mutation exists.

FCoV is a highly contagious virus. Feces are the main source of infection, with litter trays a major transmission factor within groups of cats. The infection is mainly transmitted orally, usually indirectly, after contact with objects contaminated with feces, such as litter trays, cleaning accessories (shovels, brushes, vacuum cleaners), and shoes. In addition, grooming contaminated paws after using the litter tray is also a route of contamination. As a result, transmission is mainly via the fecal-oral route.

FIP particularly affects cats of certain breeds, as well as youngsters under the age of two. In addition, a large number of cats developing FIP come from multi-cat households or have a history of being housed in such households. A recent stress factor, such as adoption, shelter stay, sterilization, upper respiratory disease, or vaccination, is frequently observed in their history. The most frequent clinical signs include effusions (usually abdominal and/or pleural, sometimes pericardial or scrotal), accompanied by fever, anorexia, and weight loss. Enlarged abdominal lymph nodes are also frequently observed, particularly in cats without effusions. Ocular symptoms (e.g. uveitis) and neurological symptoms (e.g. ataxia) may also occur.

When an effusion is present, its analysis (cytology, biochemistry, and FCoV antigen or RNA testing) is crucial to the diagnosis of FIP. In the absence of effusion, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of affected organs for cytology and FCoV RNA analysis is also useful.

Diagnosis of FIP

Treatment of FIP

The recent availability of effective antiviral treatments, notably the nucleoside analog GS-441524, has radically changed the treatment of FIP for owners and veterinary teams. Euthanasia is no longer the only option, and FIP is frequently curable. These treatments are fast-acting, enabling diagnostic treatment in cats where FIP is highly likely. Success rates ranging from 81% to 100% have been reported in cats treated with different preparations of compounds believed, or known, to contain GS-441524. Thus, veterinarians now need effective diagnostic tools to rapidly assess the likelihood of a FIP diagnosis, so that they can administer antivirals in good time.

Why is early, reliable diagnosis essential?

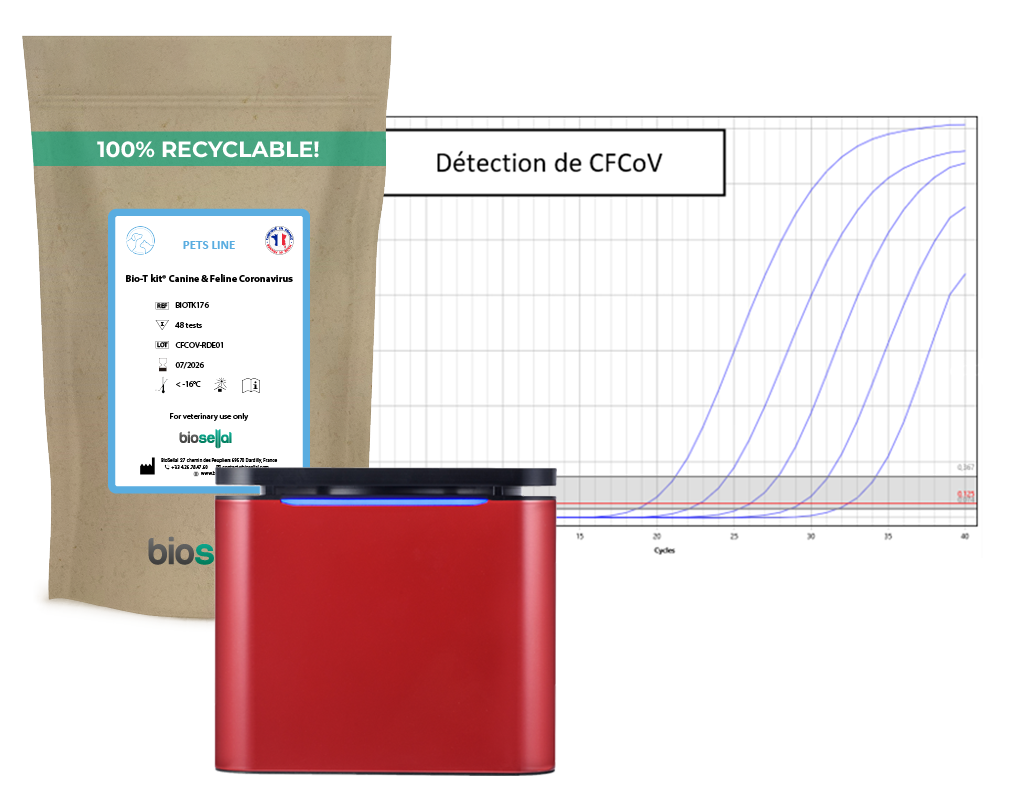

Our solution: the Bio-T kit® Canine & Feline Coronavirus

We have developed a sensitive triplex real-time PCR kit for the detection of FCoV, including the coronavirus responsible for FIP, in all matrices of interest.

Absolute quantification is integrated into the kit, enabling monitoring of disease progression and animal response to treatment.

✔ Analysis: Qualitative & quantitative for longitudinal viral load monitoring

✔ Specimen types: Whole blood (on EDTA tube), rectal swab, feces, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), pleural and peritoneal effusion fluid.

✔ Validated thermocyclers: QuantStudio™5, MIC qPCR Cycler, ELITe InGenius, AriaMx™, and others.

✔ Amplification programs: 65 minutes on standard real-time PCR thermal cyclers and 50 minutes on MIC qPCR Cycler

Why choose our kit?

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

A complete range for diagnosing infectious diseases in companion animals

The Bio-T kit® Canine & Feline Coronavirus is part of a comprehensive range of real-time PCR kits dedicated to the diagnosis of infectious diseases in companion animals. Our kits enable rapid and accurate identification of a wide range of canine and feline pathogens.

Need more information or personalized support? Our team is at your disposal to advise you and help you choose the solutions best suited to your analyses.

Addie, D.D.; Jarrett, O. Use of a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for monitoring the shedding of feline coronavirus by healthy cats. Vet. Rec. 2001, 148, 649-653.

Addie, D.D.; Jarrett, O. A study of naturally occurring feline coronavirus infections in kittens. Vet. Rec. 1992, 130, 133-137.

Kipar, A.; May, H.; Menger, S.;Weber, M.; Leukert, W.; Reinacher, M. Morphologic features and development of granulomatous vasculitis in feline infectious peritonitis. Vet. Pathol. 2005, 42, 321-330.

Zehr, J.D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Millet, J.K.; Olarte-Castillo, X.A.; Lucaci, A.G.; Shank, S.D.; Ceres, K.M.; Choi, A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Goodman, L.B.; et al. Natural selection differences detected in key protein domains between non-pathogenic and pathogenic feline coronavirus phenotypes. Virus Evol. 2023, 9, vead019.

Worthing, K.A.;Wigney, D.I.; Dhand, N.K.; Fawcett, A.; McDonagh, P.; Malik, R.; Norris, J.M. Risk factors for feline infectious peritonitis in Australian cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2012, 14, 405-412.

Yin, Y.; Li, T.;Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Ouyang, H.; Ji,W.; Liu, J.; Liao, X.; Li, J.; Hu, C. A retrospective study of clinical and laboratory features and treatment on cats highly suspected of feline infectious peritonitis in Wuhan, China. Sci. Rep. 2021,

Soma, T.;Wada, M.; Taharaguchi, S.; Tajima, T. Detection of ascitic feline coronavirus RNA from cats with clinically suspected feline infectious peritonitis. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2013, 75, 1389-1392.

Lewis, K.M.; O'Brien, R.T. Abdominal Ultrasonographic Findings AssociatedWith Feline Infectious Peritonitis: A Retrospective Review of 16 Cases. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2010, 46, 152-160.

Dunbar, D.; Kwok, W.; Graham, E.; Armitage, A.; Irvine, R.; Johnston, P.; McDonald, M.; Montgomery, D.; Nicolson, L.;Robertson, E.; et al. Diagnosis of non-effusive feline infectious peritonitis by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR from mesentericlymph node fine-needle aspirates. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 910-921.

Thayer, V.; Gogolski, S.; Felten, S.; Hartmann, K.; Kennedy, M.; Olah, G.A. 2022 AAFP/EveryCat Feline Infectious Peritonitis Diagnosis Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022,

Addie, D.; Belak, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Egberink, H.; Frymus, T.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Hartmann, K.; Hosie, M.J.; Lloret, A.;Lutz, H.; et al. Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11,594-604.

Haake, C.; Cook, S.; Pusterla, N.; Murphy, B. Coronavirus Infections in Companion Animals: Virology, Epidemiology, Clinical and Pathologic Features. Viruses 2020, 12, 1023